Getty Images

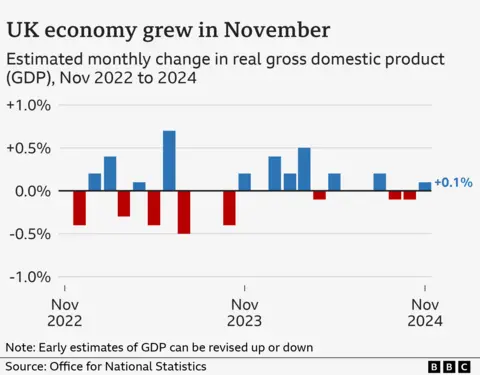

Getty ImagesThe UK economy returned to growth in November, but the expansion was less than expected.

The 0.1% uptick was driven by trade for pubs, restaurants and the construction industry, and marked the first time the economy had grown for three months after it shrank in October and September.

The figures come after recent turbulence in financial markets sent the UK’s borrowing costs to the highest level for several years and the value of the pound down.

But with tax rises coming into effect in April, the sluggish figures have fuelled further concerns that stagnant growth could persist in the UK for some time.

Chancellor Rachel Reeves, who has been under pressure after the market turmoil threatened her economic plans, admitted the government had to “do more to grow our economy” as she reiterated her pledge to go “further and faster” to improve growth in order to boost living standards.

Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer added that growing the economy was “always going to take time”, but said the return to growth in November was a “step in the right direction”.

November’s economic figures were the first following Reeves’s first Budget, in which she announced £40bn worth of tax rises with hikes in the National Insurance rate and a reduction to the threshold for employers.

Ahead of tax increases taking effect in April, businesses have repeatedly warned the extra costs they face, along with minimum wages rising and business rates relief being reduced, could impact the economy’s ability to grow, with employers expecting to have less cash to give pay rises and create new jobs.

In the three months to November, the economy is estimated to have shown no growth, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) said. It has only grown twice in the five months since Labour took office.

Danni Hewson, AJ Bell head of financial analysis, said the bigger economic picture was one of an “economy still stuck in the muck”, while Ben Jones, lead economist at the CBI business group which claims to represent 170,000 firms, said a “mood of caution seems to have settled over UK businesses”.

“We’ve had a pretty gloomy start to this year,” said Liz Martins, senior economist at HSBC. “We’re not in recession, but we’re not doing much growing either.”

In a bid to turn the tide, Reeves will meet representatives from some of the country’s biggest regulators later, including energy watchdog Ofgem and the Competitions and Markets Authority, to get ideas for growing the economy.

Reeves is understood to have decided to meet them in-person rather than wait to read submissions, with a Treasury source describing the meeting as “a kick up the backside”.

The ONS said the construction and services sectors drove the marginal growth in November.

Construction was led by new commercial developments, but Liz McKeown, director of economic statistics at ONS, said production continued to decline across several manufacturing industries and oil and gas extraction companies.

“Services grew a little, with wholesaling, pubs and restaurants and IT companies all doing well, partially offset by falls in accountancy and business rental and leasing,” she added.

The pound fell following the data release, trading at $1.221, down 0.2% on the day. Long-term government borrowing costs remained stable.

‘Put the handbrake on’

Adrian Haller, who runs the UK arm of Bruderer, a Swiss manufacturer that makes high speed presses, is preparing to open a new factory in Telford, Shropshire.

But he said the Budget “put a dampener” on the business, with some of his biggest customers more cautious after the rise in employer National Insurance contributions was announced.

“Consequently, they’ve reduced their interest in placing orders with companies like ours,” he added.

“Everybody seems to have put the handbrake on,” he said. “All that I ask, is that the government listen to what we are trying to say, and the fact they’ve done too many changes too quickly – and it’s making it difficult for us to survive.”

A growing economy usually means people are spending more, extra jobs are created, more tax is paid and workers get better pay rises.

When the economy is shrinking, it can lead to businesses cutting back on investment and jobs.

Rob Wood, chief UK economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics, said tax hikes announced in the chancellor’s October Budget and “global uncertainty” around Donald Trump’s potential tariffs on trade with the US had “dragged the economy into stagnation”.

The weaker-than-expected growth figures fuelled further expectations that the Bank of England will cut interest rates at its next meeting in February from 4.75% to 4.5%, especially after UK inflation unexpectedly dipped in December.

But Mr Wood said the outlook for 2025 was brighter than the figures were showing for 2024.

He said despite the tax rises on businesses coming in April, the economy should get a boost from Reeves “recycling increased taxes into even more spending” in 2025.