The recent electoral outcomes in Jharkhand and Maharashtra, two very different geographical terrains, reveal three common factors. First, in both States the incumbent alliances won by a huge margin. Second, despite poor performances in the Lok Sabha election held six months earlier, the ruling alliances in both States staged a dramatic recovery in the Assembly elections. Third, they benefited significantly from the implementation of women-centric direct cash transfer schemes, particularly the Mukhyamantri Maiya Samman Yojana offering Rs.1,000 a month in Jharkhand and the Mukhyamantri Majhi Ladki Bahin Yojana providing Rs.1,500 a month in Maharashtra.

Significantly, Jharkhand and Maharashtra are not the first States to implement cash transfer schemes for women. It started in West Bengal in 2021, just a few months before the Assembly election. In the 2023 Karnataka election, the Congress promised a similar scheme called the Gruha Lakshmi Scheme. The party that promised or implemented the scheme first reaped the electoral benefits.

Also Read | The myth of the ‘women vote bank’

Does this mean that women vote as a distinct electoral constituency? Do women vote more for parties that deliver or promise economic incentives specifically for them? There are indications that unlike in the past, financial assistance has helped mobilise women politically, with large-scale cash transfers or other women-centric schemes enabling them to discuss governance at home and in society.

The history of women’s participation in elections suggests three trends. First, their participation has increased tremendously. The voter turnout of men and women is now almost equal, after continuously showing a double-digit gap in the initial few decades of Independence.

At a polling booth in Sarauli village of Ghaziabad constituency in Uttar Pradesh in April 2019. Since 2014, the women’s turnout has been above 65 per cent.

| Photo Credit:

MOORTHY RV

Second, although their participation has increased, women voters’ choices have not differed significantly from that of their male counterparts. In other words, the voting patterns of women have largely been the same as that of their male counterparts.

Third, although women’s participation has increased significantly, this change has been driven from the top and not the bottom. This means that, rather than women making specific demands of political parties, the parties themselves have been wooing them with economic incentives.

Frontline addresses these three basic questions and traces how the woman voter has emerged as a mobilising factor in elections across India.

Electoral participation

In the past two Lok Sabha elections, the male and female turnout was equal; however, the journey to reach this point has been long. In the 1957 Lok Sabha election, only 39 per cent of women voted compared with 56 per cent of men. In 2024, the turnout of both men and women had risen to 66 per cent (see Chart 1). Since 1962, the male turnout has been continuously above 60 per cent, but the female turnout did not surpass the 60 per cent mark until the 1998 Lok Sabha election.

Since 2014, the women’s turnout has been above 65 per cent. Although women’s participation has steadily increased over the years, there have been a few occasions when it increased significantly: 1977, 1984, 1998, and 2014. Except in 1984, when the sympathy wave following the death of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi played a role, the incumbent party has lost power in all other occasions.

Women’s mobilisation in the Indian electoral system has been a top-down phenomenon, with them responding to political leaders and parties making promises or decisions in favour of women; women have not made any aggressive demands of the state. In the 1970s and 1980s, a period of rights-based movements across the world, the major demand from women in India was for suraksha (safety) from crimes such as rape. As such, for a long time, politicians and parties focussed on public safety to win women over. Parties such as the Janata Dal (United) in Bihar and the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) in Uttar Pradesh focussed on law and order issues to gain women’s support.

In 2007, Nitish Kumar launched the Mukhyamantri Balika Cycle Yojana providing free bicycles to every girl child in class IX to prevent them from dropping out of school after a certain age. In the picture, beneficiaries of the scheme on the outskirts of Patna in 2018.

| Photo Credit:

RANJEET KUMAR

From 2005 to 2020, State and Central governments began to prioritise women’s education and health along with safety. Leaders such as M.G. Ramachandran (MGR) and Jayalalithaa (Tamil Nadu), Nitish Kumar (Bihar), Mamata Banerjee (West Bengal), and Shivraj Singh Chouhan (Madhya Pradesh) focussed on increasing the enrolment of girls in schools and on women’s health, especially in reducing mortality among girl children. In 1982, as Chief Minister, MGR targeted mothers by promising nutrition in schools and encouraging them to enroll their children. This he did by extending the noon-meal scheme that had existed in some form since the 1920s to cover children in the age group of 2-5 years in anganwadis and those aged 5-9 years in primary schools in rural areas.

Bihar, Odisha, and West Bengal followed suit and implemented many schemes to promote the girl child and increase their enrolment in schools. In 2007, Nitish Kumar launched the Mukhyamantri Balika Cycle Yojana providing free bicycles to every girl child in class IX to prevent girl students from dropping out of school after a certain age.

Nitish Kumar went on to launch the Mukhyamantri Kanya Utthan Yojana in 2018 providing Rs.1,000 to every girl completing class XII, Rs.50,000 upon graduation, and Rs.2,000 for sanitary napkins annually. He also banned the use of alcohol in Bihar, which helped him win the election. In the tightly contested Assembly election in 2020, it was women voters who helped him overcome a huge anti-incumbency wave.

A survey conducted by the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS) in 2020 shows that although the Mahagathbandhan, led by the Rashtriya Janata Dal, had a 1 percentage point lead over the Nitish Kumar-led National Democratic Alliance (NDA) among men, Nitish Kumar had a 2 percentage point lead among women voters. Another significant data point suggests that the Mahagathbandhan had a 6 percentage point edge among youths (aged 18-29 years), while the NDA had a 4 percentage point edge among young women. According to a news report, there was a 5 percentage point lead for the NDA among women aged 30-39 years (The Indian Express, November 19, 2020).

West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee at an event to mark 10 years of Kanyashree Prakalpa, a flagship scheme of the Trinamool Congress government for girl empowerment.

| Photo Credit:

DEBASISH BHADURI

Similarly, in West Bengal, Mamata Banerjee launched schemes such as the Kanyashree Prakalpa (2013), the Rupashree Prakalpa (2018), and the Lakshmir Bhandar (2021) targeting women voters. In the 2021 Assembly election, women supported Mamata overwhelmingly; the BJP could not depose the Trinamool government despite its good performance in the 2019 Lok Sabha election. The CSDS post-election data reveal that the Trinamool Congress had a 13 percentage point lead over the BJP among women. Even in the 2021 election, 4 per cent more women voted for the Trinamool than men.

At the national level, the Narendra Modi government also launched schemes such as the Pradhan Mantri Jan-Dhan Yojana (2014), the Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana (2016), and the Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana (2017) to assist and empower women.

Significantly, the focus of political parties in the past few years has shifted from safety and schooling to financial assistance schemes. The main trigger for the BJP to turn its attention to financial assistance was the NYAY (Nyuntam Aay Yojana) schemes the Congress party promised in the 2019 Lok Sabha election to provide poor households with financial assistance of Rs.72,000 annually.

Highlights

- Women’s electoral participation has increased significantly, with voter turnout now almost equal to that of men. In some States, women even outnumber men at polling booths, reflecting a steady rise in their engagement with electoral democracy.

- Political parties have increasingly used women-centric welfare schemes to mobilise women voters. The Mukhyamantri Maiya Samman Yojana in Jharkhand and the Mukhyamantri Majhi Ladki Bahin Yojana in Maharashtra helped the incumbent governments reap electoral benefits.

- Increased participation of women in electoral politics signals anew democratic upsurge, which will shift the political discourse from being male-dominated to being more equitable. However, women have to begin to vote on the pressing issues that concern them for real woman-oriented polity.

It was the Jan-Dhan scheme that enabled even the poor to open bank accounts with minimum requirements, thus paving the way for large-scale cash transfers by the government. In the past, incentives or subsidies were common strategies. For instance, Jayalalithaa was renowned for announcing schemes during election campaigns, like free mixer grinders or a 50 per cent subsidy for buying mopeds, which helped her garner significant electoral support from women.

From 2019 onwards, across parties, governments have increasingly announced direct cash transfers. The BJP, which had proclaimed that it was reluctant to increase the economic burden on the exchequer, was the first to launch such schemes. Just a few months before the 2019 Lok Sabha election, Modi announced the Kisan Samman Nidhi providing financial assistance to farmers. Later, the BJP-led government in Haryana announced the Berojgari Bhatta Yojana providing an unemployment allowance to educated women—a monthly allowance of Rs.1,500 for graduates and Rs.3,000 for postgraduates.

Why target women?

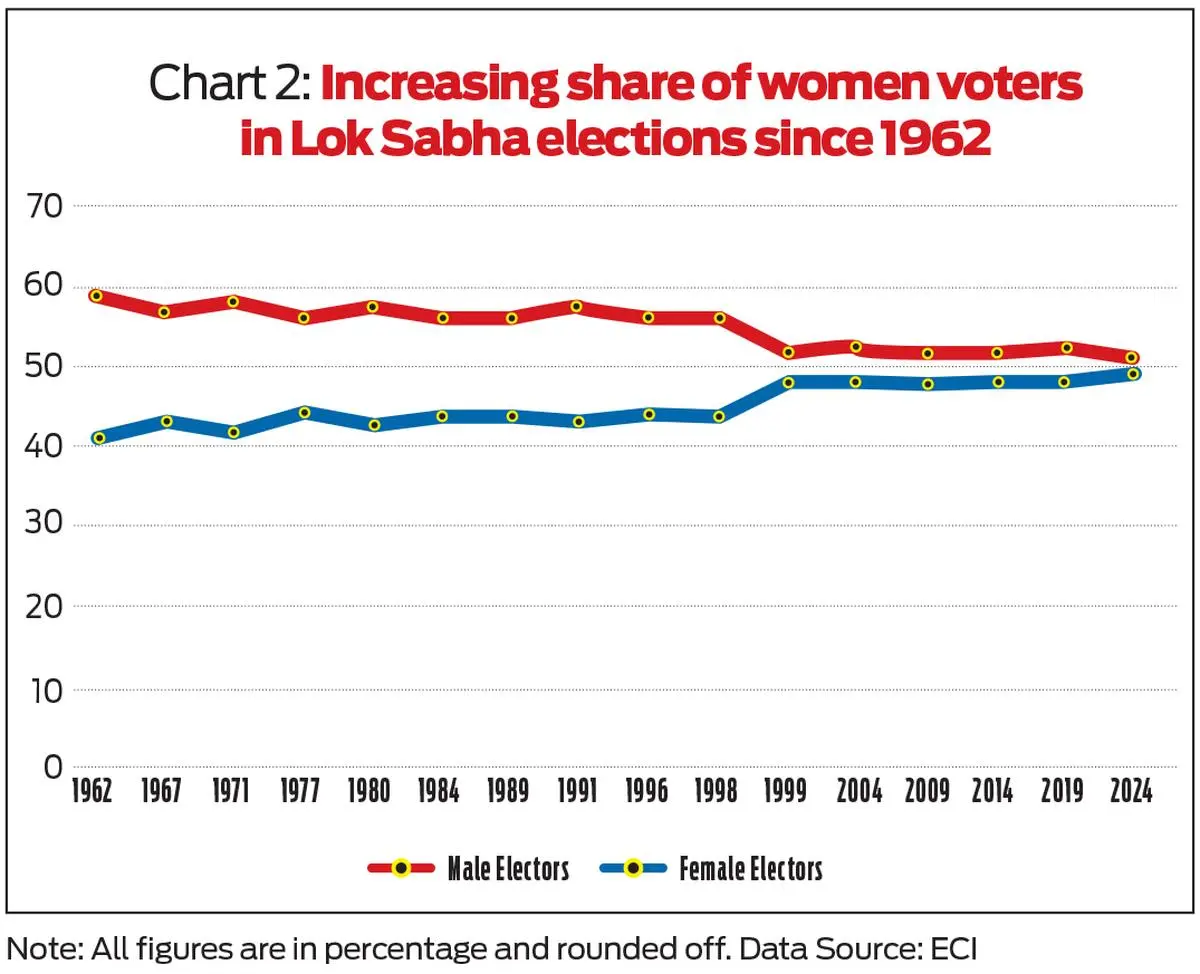

In 1962, women made up only 40 per cent of the total voters. Even in the 1998 Lok Sabha election, this rose to 45 per cent. The gender gap was in double digits (10 per cent) until 2004, but since 2009 it has changed significantly, and the gap has narrowed steadily. In the 2024 Lok Sabha election, the gap was reduced to just 1 per cent (see Chart 2).

Chart 2 suggests that not only women’s turnout during elections but also women’s participation in elections has increased significantly in the past two decades, bringing their numbers close to that of men. Expectedly, the growth rate of women voters in recent years has surpassed that of men. In the last two Lok Sabha elections, the growth rate of women was 2 percentage points more than men (see Chart 3).

Overall, there has been an increase in enrolment in electoral rolls, the growth rate of women voters, and their turnout. In some States, women have outnumbered men in polling booths. These three data points suggest that women are more active during elections than in the past. The drivers of this change could be many: increased women’s representation at local levels of governance, initiatives such as SVEEP (Systematic Voter’s Education and Electoral Participation) led by the Election Commission of India, and the transactional benefits inherent in the process. All these appear to have attracted more women to participate in electoral democracy.

Since women’s share is almost half of the total electorate, a few percentage points inclination towards any political party/alliance could lead to a significant change in the electoral outcome.

Conclusion

As their numbers increase, the influence of women voters is likely to grow significantly. The results suggest that women prioritise transactional benefits and do not carry any ideological burden. However, it would be a mistake to interpret this to mean they have no interest in the politics of identity. They seem to respond positively to cash benefits, which is why welfare schemes have yielded electoral dividends for parties.

In India’s highly patriarchal society, any kind of direct cash transfer empowers women. And the digitisation measures have enabled all political parties to reach women beneficiaries directly, without the help of male intermediaries.

In the 2015 Bihar Assembly election, for instance, this writer met a female senior citizen in Saharsha who said she would vote for Nitish Kumar as he had provided Rs.500 a month as old-age pension. This meant, she said, that she did not have to depend on her son to eat bari (fried savoury).

Also Read | Editor’s Note: The Machiavellian manipulation of mahila schemes

In another instance, during this writer’s fieldwork in the 2024 Jharkhand Assembly election, a woman in her early 30s said she had voted for Modi in the Lok Sabha election as she had eaten Modi ka ration (5 kg free grain) but that in the Assembly election she would vote for Hemant Soren, who had delivered Rs.1,000 under the Maiya Samman scheme.

Jayalalithaa introduced schemes aimed at women like free mixer-grinders and 50 per cent subsidy for buying mopeds. In picture, a beneficiary with a moped given by the State government.

| Photo Credit:

SATHYAMOORTHY M

Any benefit that targets women empowers them economically, politically, and socially. The 73rd Constitutional Amendment gave one-third (in some places 50 per cent) reservation for women in panchayats, the one-third reservation in jobs (for example, Bihar), and now the cash transfer schemes have empowered women in several, often undocumented, ways. These have given women a new yardstick with which to evaluate parties rather than fall back on communal and identity-based sentiments. However, it is still not clear whether they vote as a bloc or along traditional caste and community lines.

The caveat is that increased cash transfers will lead to an increased financial burden on the exchequer, with all parties trying to up the ante. This is not a long-term sustainable plan and will invariably benefit the incumbent government, which holds the purse strings, the most.

Of course, the larger trend—that of increased participation of women in electoral politics—signals a new democratic upsurge, which will shift the political discourse from being male-dominated to being more equitable. However, it is only when women begin to vote on the pressing issues that concern them that we will see a real woman-oriented polity.

Ashish Ranjan is an election researcher and co-founder of the Data Action Lab for Emerging Societies (DALES).