Europe’s big new rocket, Ariane-6, has blasted off on its maiden flight.

The vehicle set off from a launchpad in French Guiana at 16:00 local time (19:00 GMT) on a demonstration mission to put a clutch of satellites in orbit.

Crews on the ground in Kourou applauded as the rocket – developed at a cost of €4bn (£3.4bn) – soared into the sky.

But after climbing smoothly to the desired altitude, and correctly releasing a number of small satellites, the upper-stage of the rocket experienced an anomaly right at the end of the flight.

Computers onboard took the decision to prematurely shut down the auxiliary power unit (APU) that pressurises the propulsion system.

This left Ariane’s upper-stage unable to initiate the burn that was supposed to bring it out of orbit and also set up the final task of the mission – to jettison two re-entry capsules.

Controllers were unable to remedy the situation, but the flight was nonetheless still declared a success.

“We’re relieved; we’re excited,” said Josef Aschbacher, the director general of the European Space Agency.

“This is a historic moment. The inaugural launch of a new heavy-lift rocket doesn’t happen every year; it happens only every 20 years or maybe 30 years. And today we have launched Ariane-6 successfully,” he told reporters.

Ariane-6 is intended to be a workhorse rocket that gives European governments and companies access to space independently from the rest of the world. It already has a backlog of launch contracts, but there are worries its design could limit future prospects.

Like its predecessor, Ariane-5, the new model is expendable – a new rocket is needed for every mission, whereas the latest American vehicles are being built to be wholly or partially reusable.

Even so, European space officials believe Ariane-6 can carve out a niche for itself.

On the surface, the 6 looks very similar to the old 5, but under the skin it harnesses state-of-the-art manufacturing techniques (3D printing, friction stir welding, augmented reality design, etc) that should result in faster and cheaper production.

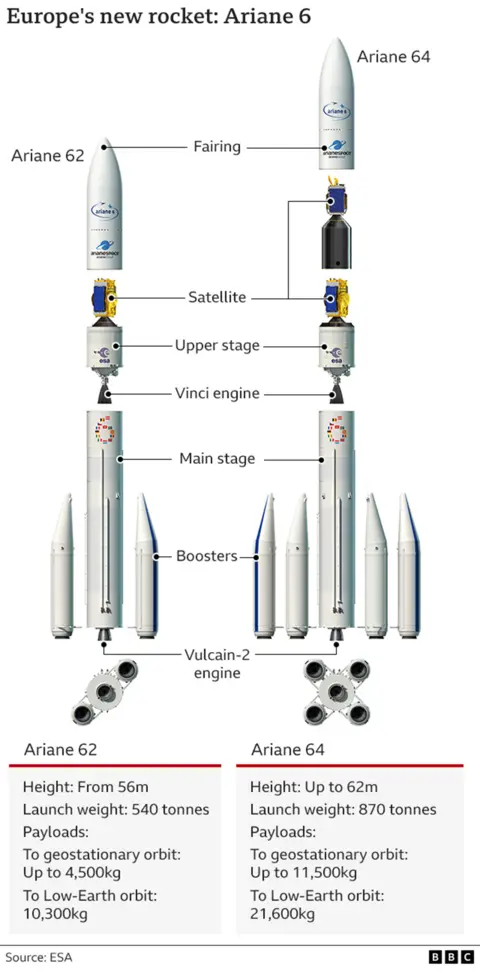

Ariane-6 will operate in two configurations:

- The “62” will incorporate two solid-fuel side boosters for lifting medium-sized payloads

- The “64” will have four strap-on boosters to lift the heaviest satellites on the market

The core stage is supplemented with a second, or upper, stage that will place the payloads in their precise orbits high above the Earth.

This stage has the new capability to be stopped and restarted multiple times, which is useful when launching large batches of satellites into a constellation, or network.

Re-ignition should also enable the stage to pull itself back down to Earth, so it won’t become a piece of lingering space junk.

The fact that the inaugural flight was unable to demonstrate this will be a disappointment to engineers, but shouldn’t hold up the Ariane-6 programme.

“A lot of missions do not need to be restarted in microgravity. This is a flexibility we could use or not, and we will adapt the flight profile depending on what we find in the data,” said Martin Sion, the chief executive of rocket manufacturer ArianeGroup.

“And to be 100% clear, we are prepared to make a second launch this year and six next year,” added Stéphane Israël from Arianespace, the company that markets the new rocket.

ESA

ESAAriane 6 vs Falcon 9

Inaugural flights are always occasions of high jeopardy. It’s not uncommon for a new rocket design to have some sort of anomaly or outright failure.

Ariane-5 famously blew itself apart 37 seconds after leaving the ground on its debut in 1996. The loss was put down to an error in control software.

But a revised rocket then came back to dominate the commercial launch market for the world’s biggest satellites.

That dominance was only broken in the 2010s by US entrepreneur Elon Musk and his reusable Falcon-9 rockets.

Falcon flight rates and prices undercut the competitiveness of Ariane-5.

AFP

AFPEurope is moving towards reusability, but the necessary technologies will not be in service until the 2030s. And in the meantime, Mr Musk is introducing even bigger rockets that promise to reduce launch costs still further.

Ariane-6 enters a very challenging environment, therefore.

“We can all have our own opinions. What I can just reaffirm is that we have an order book that is full,” said Lucia Linares, who heads space transportation strategy at Esa.

“I guess the word goes here to the customers: they have said Ariane-6 is an answer to their needs.”

ARIANEGROUP

ARIANEGROUPThere are launch contracts to take the rocket through its first three years of operations. These include 18 launches for another US billionaire, Jeff Bezos, who wants to establish a constellation of internet satellites he calls Kuiper.

European officials aim to have Ariane-6 flying roughly once a month.

If this flight rate can be achieved, then the rocket should be able to establish itself, commented Pierre Lionnet from space consultancy ASD Eurospace.

“First, we need to ensure that there is sufficient demand from European customers – the European institutional ones. Then Ariane needs to win just a few commercial customers beyond Kuiper. This would give it a market,” he told BBC News.

“But it’s a matter of pricing. If Falcon-9 is systematically undercutting the price offer of Ariane-6, there will be an issue.”

Ariane-6 is a project of 13 member states of Esa, led by France (56%) and Germany (21%). The 13 partners have promised subsidy payments of up to €340m (£295m) a year to support the early phase of Ariane-6 exploitation.

The UK was a leading player right at the beginning of Europe’s launcher programme and remains an Esa member state, but its direct involvement in Ariane ended when the Ariane-4 model was retired, in 2003.

A few UK companies continue to supply components on a commercial basis, and some spacecraft built in Britain will undoubtedly continue to fly on Ariane.

Reuters

Reuters